Complex organic molecules discovered in infant star system

April 7, 2015

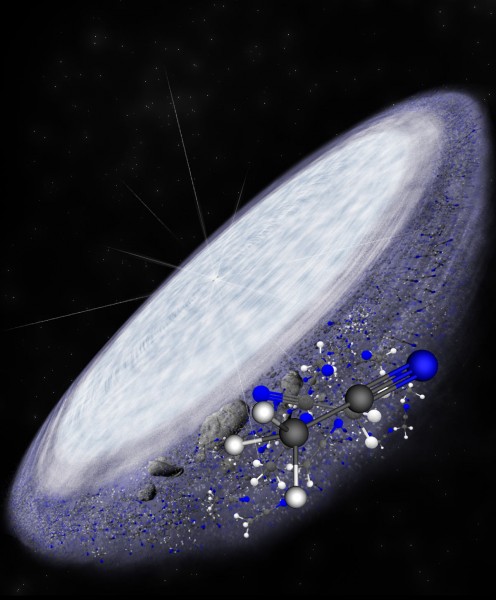

Artist impression of the protoplanetary disk surrounding the young star MWC 480. ALMA has detected the complex organic molecule methyl cyanide in the outer reaches of the disk in the region where comets are believed to form. This is another indication that complex organic chemistry, and potentially the conditions necessary for life, is universal. (credit: B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF))

For the first time, astronomers have detected the presence of complex organic molecules, the building blocks of life, in a protoplanetary disk surrounding a young star, suggesting once again that the conditions that spawned our Earth and Sun are not unique in the universe.

This discovery, made with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), reveals that the protoplanetary disk surrounding the million-year-old star MWC 480 is brimming with methyl cyanide (CH3CN), a complex carbon-based molecule, and and its simpler cousin hydrogen cyanide (HCN).

The molecules were found in the cold outer reaches of the star’s newly formed disk, in a region that astronomers believe is analogous to our own Kuiper Belt — the realm of icy planetesimals and comets beyond Neptune.

Comets retain a pristine record of the early chemistry of our solar system from the period of planet formation. As the planets evolved, it’s believed that comets and asteroids from the outer solar system seeded the young Earth with water and organic molecules, helping set the stage for life to eventually emerge.

“Studies of comets and asteroids show that the solar nebula that spawned our Sun and planets was rich in water and complex organic compounds,” noted Karin Öberg, an astronomer with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., and lead author on a paper published in the journal Nature.

“We now have evidence that this same chemistry exists elsewhere in the universe, in regions that could form solar systems not unlike our own.” This is particularly intriguing, Öberg notes, since the molecules found in MWC 480 are also found in similar concentrations in our own solar system’s comets.

The star MWC 480, which is about twice the mass of the Sun, is located approximately 455 light-years away in the Taurus star-forming region. Its surrounding disk is in the very early stages of development, having recently coalesced out of a cold, dark nebula of dust and gas. Studies with ALMA and other telescopes have yet to detect any obvious signs of planet formation in it, though higher-resolution observations may reveal structures similar to HL Tau, which is of a similar age.

Astronomers have known that cold, dark interstellar clouds are very efficient factories of complex organic molecules — including a group of molecules known as cyanides. Cyanides, and most especially methyl cyanide, are important because they contain carbon-nitrogen bonds, which are essential for the formation of amino acids, the foundation of proteins.

Complex organic molecules found to survive in newly forming solar systems

It has been unclear, however, if these same complex organic molecules commonly form and survive in the energetic environment of a newly forming solar system, where shocks and radiation can easily break chemical bonds. With ALMA’s remarkable sensitivity, the astronomers now know that these molecules not only survive, but thrive.

Importantly, the molecules ALMA detected are much more abundant than would be found in interstellar clouds. According to the researchers, there’s enough methyl cyanide around MWC 480 to fill all of Earth’s oceans. This tells astronomers that protoplanetary disks are very efficient at forming complex organic molecules and that they are able to form them on a relatively fast timescale.

This rapid formation is essential to outpace the forces that would otherwise break the molecules apart. Also, these molecules were detected in a relatively serene part of the disk, roughly 4.5 to 15 billion kilometers from the central star. Though incredibly distant by our solar system’s standards, in MWC 480’s scaled-up dimensions, this would be squarely in the comet-forming zone.

As this solar system continues to evolve, astronomers speculate, it’s likely that the organic molecules safely locked away in comets and other icy bodies will be ferried to environments that would be more nurturing for life.

“From the study of exoplanets, we know our solar system isn’t unique in having rocky planets and an abundance of water,” concluded Öberg. “Now we know we’re not unique in organic chemistry. Once more, we have learned that we’re not special. From a life in the universe point of view, this is great news.”

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile, is the largest astronomical project in existence. ALMA is a single telescope of revolutionary design, composed initially of 66 high precision antennas located on the Chajnantor plateau, 5000 meters altitude in northern Chile.

Abstract of The cometary composition of a protoplanetary disk as revealed by complex cyanides

Observations of comets and asteroids show that the Solar Nebula that spawned our planetary system was rich in water and organic molecules. Bombardment brought these organics to the young Earth’s surface, seeding its early chemistry. Unlike asteroids, comets preserve a nearly pristine record of the Solar Nebula composition. The presence of cyanides in comets, including 0.01% of methyl cyanide (CH3CN) with respect to water, is of special interest because of the importance of C-N bonds for abiotic amino acid synthesis. Comet-like compositions of simple and complex volatiles are found in protostars, and can be readily explained by a combination of gas-phase chemistry to form e.g. HCN and an active ice-phase chemistry on grain surfaces that advances complexity. Simple volatiles, including water and HCN, have been detected previously in Solar Nebula analogues – protoplanetary disks around young stars – indicating that they survive disk formation or are reformed in situ. It has been hitherto unclear whether the same holds for more complex organic molecules outside of the Solar Nebula, since recent observations show a dramatic change in the chemistry at the boundary between nascent envelopes and young disks due to accretion shocks. Here we report the detection of CH3CN (and HCN and HC3N) in the protoplanetary disk around the young star MWC 480. We find abundance ratios of these N-bearing organics in the gas-phase similar to comets, which suggests an even higher relative abundance of complex cyanides in the disk ice. This implies that complex organics accompany simpler volatiles in protoplanetary disks, and that the rich organic chemistry of the Solar Nebula was not unique.