Dramatic remissions in blood cancer in immunotherapy treatment trial

March 10, 2016

*****UPDATE JULY 12, 2016*****

Juno Therapeutics, Inc. announced July 7 that it has received notice from the FDA that it has placed a clinical hold on an immune-cell cancer treatment known as the “ROCKET” trial, which was reported on KurzweilAI on Mar. 10, 2016.

The clinical hold was initiated after two patient deaths, which followed the recent addition of fludarabine to the pre-conditioning regimen. Juno has proposed to the FDA to continue the ROCKET trial using JCAR015 with cyclophosphamide pre-conditioning alone.

Further information on Forbes.

**********

Recent advances in an immune-cell cancer treatment — a type of immunotherapy* using engineered immune cells to target specific molecules on cancer cells — are producing dramatic results for people with cancer, according to Stanley Riddell, MD, an immunotherapy researcher and oncologist at Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.**

Riddell and his colleagues have refined new methods of engineering a patient’s own immune cells to better target and kill cancer cells while decreasing side effects. In laboratory and clinical trials, the researchers are seeing “dramatic responses” in patients with tumors that are resistant to conventional high-dose chemotherapy, “providing new hope for patients with many different kinds of malignancies,” Riddell said.

Fred Hutch | Immunotherapy shows great promise

Twenty-seven out of 29 patients with an advanced blood cancer who received experimental, “living” immunotherapy as part of a clinical trial experienced sustained remissions, in preliminary results of an ongoing study at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Boosting natural immune response

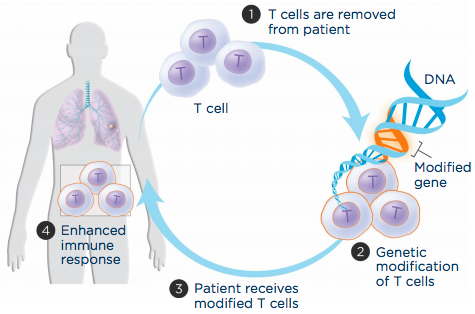

Adoptive T-cell transfer aims to boost a patient’s immune cells’ ability to recognize and attack cancer cells. (1) T cells are extracted from the patient’s blood, (2) genetically engineered to produce a molecule that recognizes cancer cells and grown in the laboratory, and (3) infused back into the patient to (4) improve immune response. (credit: LUNGevity Foundation)

The immune system produces two major types of immune reaction to protect the body: one uses antibodies secreted by B cells; the other uses T cells.

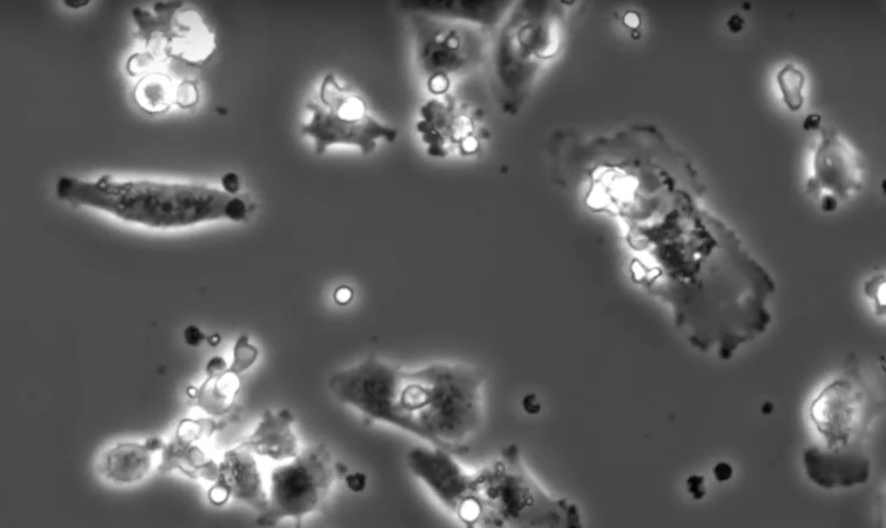

Riddell’s team takes T cells from the patient’s body, re-engineers them, and infuses them back into the patient to create an army of cancer-fighting immune cells. (credit: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

T cells are white blood cells that detect foreign or abnormal cells — including cancerous or infected cells — and initiate a process that targets those cells for attack. But the natural immune response to a tumor is often neither potent nor persistent enough, so Riddell and associates pioneered a new way to boost this immune response using a method known as “adoptive T-cell transfer.”

With adoptive T-cell transfer, immune cells are engineered to recognize and attack the patient’s cancer cells. Researchers extract T cells from a patient’s blood and then introduce genes into those T cells so they synthesize highly potent receptors (called chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs) that can recognize and target the cancer cell.

A single treatment of a relatively small number of the re-engineered T cells only takes about 30 minutes, and within weeks, the patient goes into a complete remission. (credit: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

They grow the T cells in a laboratory for about two weeks and then infuse the engineered cells back into the patient, where they can home in on the tumor site and destroy the cancer cells.

Sustained remission of B cell cancers

Riddell’s team has recently developed a refined version of this process that increases the effectiveness of the immune response while reducing negative side effects, such as neurological symptoms, fevers, and large decreases in blood pressure.

In a study published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, Riddell and his team describe tagging the potent T-cell receptor (with amino acid sequences called Strep-tag), and the resulting effect on human cancer cells in the laboratory and on a mouse model of lymphoma.

Those results, using the latest version of this experimental immunotherapy, suggest sustained remission in cases of B cell cancers that previously relapsed and had become resistant to treatment.***

“The results are simply astounding,” Riddell said. We are treating patients with advanced leukemia and lymphoma that have failed every conventional therapy and radiation therapy, including transplants … in a single treatment. Within weeks, the patient goes into remission.”

“In my years as a oncologist and as a research scientist, I have never seen a treatment that has that spectacular response rate in its initial testing in patients,” Riddell said. His team is initiating trials in lung, breast, sarcoma, melanoma, and soon in pancreatic cancer. The opportunities for this technology are “incredible” and the approach has the potential to also treat common cancers such as kidney and colon cancer, he said.

“We are at the precipice of a revolution in cancer treatment based on using immunotherapy.”

Funding for Riddell’s research was provided by Juno Therapeutics.

* For approximately 100 years, the main tools to treat cancer were surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. But since around 2000, doctors have had access to a type of immunotherapy based on engineered antibodies that can target specific molecules on cancer cells. For example, trastuzumab (Herceptin) can be used for some types of breast cancer and stomach cancer. The new treatment approach used by Riddell’s team is based on a new type of immunotherapy using engineered immune cells to kill cancer, rather than antibodies.

*** Such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Abstract of Acquisition of a CD19 negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T cell therapy

Administration of lymphodepletion chemotherapy followed by CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells is a remarkably effective approach to treat patients with relapsed and refractory CD19+ B cell malignancies. We treated 7 patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) harboring rearrangement of the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene with CD19 CAR-T cells. All patients achieved complete remission in the bone marrow by flow cytometry after CD19 CAR-T cell therapy; however, within one month of CAR-T cell infusion two of the patients developed acute myeloid leukemia that was clonally related to their B-ALL, a novel mechanism of CD19-negative immune escape. These reports have implications for the management of patients with relapsed and refractory MLL-B-ALL who receive CD19 CAR-T cell therapy.

Abstract of Inclusion of Strep-tag II in design of antigen receptors for T-cell immunotherapy

Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells has the potential to treat cancer and other diseases. The introduction of Strep-tag II sequences into specific sites in synthetic chimeric antigen receptors or natural T-cell receptors of diverse specificities provides engineered T cells with a marker for identification and rapid purification, a method for tailoring spacer length of chimeric receptors for optimal function, and a functional element for selective antibody-coated, microbead-driven, large-scale expansion. These receptor designs facilitate cGMP manufacturing of pure populations of engineered T cells for adoptive T-cell therapies and enable in vivo tracking and retrieval of transferred cells for downstream research applications.