Engineers design enhanced magnetic protein nanoparticles to better track cells

November 3, 2015

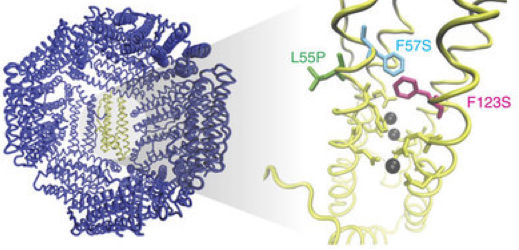

X-ray crystal structure of iron storage ferritin PFt displaying the internal cavity of the protein in which one of the subunits is highlighted in yellow (credit: Yuri Matsumoto/Nature Communications)

MIT engineers have designed magnetic protein nanoparticles that can be used to track cells or to monitor interactions within cells. The particles, described Monday (Nov. 2) in an open-access paper in Nature Communications, are an enhanced version of a naturally occurring, weakly magnetic protein called ferritin.

“We used the tools of protein engineering to try to boost the magnetic characteristics of this protein,” says Alan Jasanoff, an MIT professor of biological engineering and the paper’s senior author.

The new “hypermagnetic” protein nanoparticles can be produced within cells, allowing the cells to be imaged or sorted using magnetic techniques. This eliminates the need to tag cells with synthetic particles and allows the particles to sense other molecules inside cells.

Genetically encoded magnetic particles

Previous research has yielded synthetic magnetic particles for imaging or tracking cells, but it can be difficult to deliver these particles into the target cells.

In the new study, Jasanoff and colleagues set out to create magnetic particles that are genetically encoded. With this approach, the researchers deliver a gene for a magnetic protein into the target cells, prompting the cells to start producing the protein on their own.

“Rather than actually making a nanoparticle in the lab and attaching it to cells or injecting it into cells, all we have to do is introduce a gene that encodes this protein,” says Jasanoff, who is also an associate member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research.

As a starting point, the researchers used ferritin, which carries a supply of iron atoms that every cell needs as components of metabolic enzymes. In hopes of creating a more magnetic version of ferritin, the researchers created about 10 million variants and tested them in yeast cells.

After repeated rounds of screening, the researchers used one of the most promising candidates to create a magnetic sensor consisting of enhanced ferritin modified with a protein tag that binds with another protein called streptavidin. This allowed them to detect whether streptavidin was present in yeast cells; however, this approach could also be tailored to target other interactions.

The mutated protein appears to successfully overcome one of the key shortcomings of natural ferritin: it’s difficult to load with iron, says Alan Koretsky, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

“To be able to make more magnetic indicators for MRI would be fabulous, and this is an important step toward making that type of indicator more robust,” says Koretsky, who was not part of the research team.

Sensing cell signals

Because the engineered ferritins are genetically encoded, they can be manufactured within cells that are programmed to make them respond only under certain circumstances, such as when the cell receives some kind of external signal, when it divides, or when it differentiates into another type of cell. Researchers could track this activity using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), potentially allowing them to observe communication between neurons, activation of immune cells, or stem cell differentiation, among other phenomena.

Such sensors could also be used to monitor the effectiveness of stem cell therapies, Jasanoff says.

“As stem cell therapies are developed, it’s going to be necessary to have noninvasive tools that enable you to measure them,” he says. Without this kind of monitoring, it would be difficult to determine what effect the treatment is having, or why it might not be working.

The researchers are now working on adapting the magnetic sensors to work in mammalian cells. They are also trying to make the engineered ferritin even more strongly magnetic.

Abstract of Engineering intracellular biomineralization and biosensing by a magnetic protein

Remote measurement and manipulation of biological systems can be achieved using magnetic techniques, but a missing link is the availability of highly magnetic handles on cellular or molecular function. Here we address this need by using high-throughput genetic screening in yeast to select variants of the iron storage ferritin (Ft) that display enhanced iron accumulation under physiological conditions. Expression of Ft mutants selected from a library of 107 variants induces threefold greater cellular iron loading than mammalian heavy chain Ft, over fivefold higher contrast in magnetic resonance imaging, and robust retention on magnetic separation columns. Mechanistic studies of mutant Ft proteins indicate that improved magnetism arises in part from increased iron oxide nucleation efficiency. Molecular-level iron loading in engineered Ft enables detection of individual particles inside cells and facilitates creation of Ft-based intracellular magnetic devices. We demonstrate construction of a magnetic sensor actuated by gene expression in yeast.