How a choice of social learning networks can make us smarter

November 15, 2013

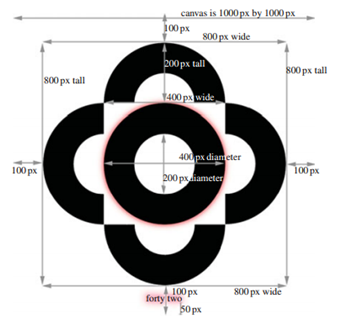

Experiment 1: participants with little or no prior experience in image editing were asked to recreate this target image using a complex editing program called GIMP (credit: Michael Muthukrishna et al., Proceedings of the Royal Academy: Biological Sciences)

The secret to why some cultures thrive and others disappear may lie in our social networks* and our ability to imitate, rather than our individual smarts, according to a new University of British Columbia study.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Academy: Biological Sciences (open access), shows that when people can observe and learn from a wider range of teachers, groups can better maintain technical skills and even increase the group’s average skill over successive generations.

The findings show that a larger population size and social connectedness are crucial for the development of more sophisticated technologies and cultural knowledge, says lead author Michael Muthukrishna, a PhD student in UBC’s Dept. of Psychology.

“This is the first study to demonstrate in a laboratory setting what archeologists and evolutionary theorists have long suggested: that there is an important link between a society’s sociality and the sophistication of its technology,” says Muthukrishna, who co-authored the research with UBC Prof. Joseph Henrich.

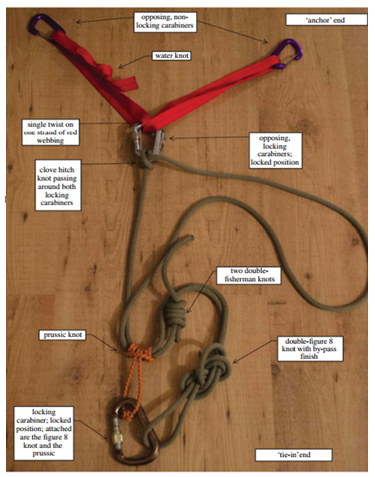

Experiment 2: participants were asked to tie a system of

connected knots commonly used in rock-climbing (credit: Michael Muthukrishna et al., Proceedings of the Royal Academy: Biological Sciences)

Learning new skills

For the study, participants were asked to learn new skills — digital photo editing and knot-tying — and then pass on what they learned to the next “generation” of participants.

The groups with greater access to experts accumulated significantly more skill than those with less access to teachers. Within ten “generations,” each member of the group with multiple mentors had stronger skills than the group limited to a single mentor.

Groups with greater access to experts also retained their skills much longer than groups who began with less access to mentors, sustaining higher levels of “cultural knowledge” over multiple generations.

According to the researchers, the study has important implications for several areas, from skills development and education to protecting endangered languages and cultural practices.

More important than innate intelligence

“People often assume that the success of our species is based on innate intelligence,” Muthukrishna explained to KurzweilAI.

“These results suggest that rather than our individual intelligence, it is our sociality — being embedded in large, well-connected populations — that explains our success. In the modern world, innovations like the Internet and online social networks can support these processes by giving us access to an unprecedented number of people and their ideas.

“An example of an application of this research might be in how we design models of mentorship to facilitate cultural transmission in a company. Although a mentor-protege model is very common, our research suggests that giving people access to multiple mentors might result in better outcomes.”

* The study authors’ choice of the word “sociality” and my choice of “social networks” in the title may be misleading. The study did not address socialization in general, or presentation of learning materials to the public. Just the opposite: It was focused on measuring improvements with learners who have access to a variety of different instructional methods: “Experiment 1 demonstrates that naive participants who could observe five models [are able to] integrate this information and generate increasingly effective skills (using an image editing tool) over 10 laboratory generations, whereas those with access to only one model show no improvement.” This has nothing to do with socialization, public presentations, or social networks such as Facebook. I modified the title, which may also help. I might point out that traditional education tends of focus on a single model — or at most, a few fixed — models without much student choice, which is shown to be ineffective in this particular experiment (but generalizing the findings to schools would be more difficult). — Editor

Abstract of Proceedings of the Royal Academy: Biological Sciences paper

Archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence suggests a link between a population’s size and structure, and the diversity or sophistication of its toolkits or technologies. Addressing these patterns, several evolutionary models predict that both the size and social interconnectedness of populations can contribute to the complexity of its cultural repertoire. Some models also predict that a sudden loss of sociality or of population will result in subsequent losses of useful skills/technologies. Here, we test these predictions with two experiments that permit learners to access either one or five models (teachers). Experiment 1 demonstrates that naive participants who could observe five models, integrate this information and generate increasingly effective skills (using an image editing tool) over 10 laboratory generations, whereas those with access to only one model show no improvement. Experiment 2, which began with a generation of trained experts, shows how learners with access to only one model lose skills (in knot-tying) more rapidly than those with access to five models. In the final generation of both experiments, all participants with access to five models demonstrate superior skills to those with access to only one model. These results support theoretical predictions linking sociality to cumulative cultural evolution.