Inquisitive robot uses arms, location and more to discover objects

May 8, 2013

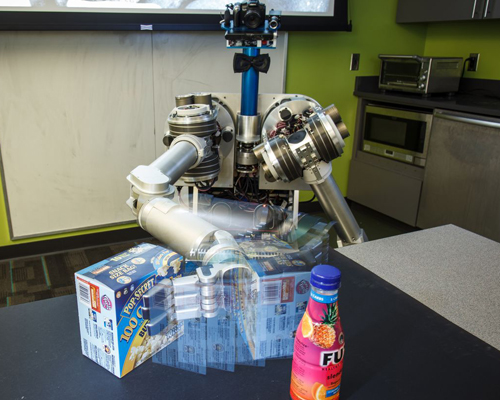

HERB can use its arms to gain information that it can use to discover objects and determine how it can pick up or manipulate that object. By using all of the information available to it, visual or otherwise, HERB is able to continually discover objects on its own and refine its understanding of those objects as it gains experience. (Credit: Carnegie Mellon University)

HERB (Home-Exploring Robot Butler) is new class of robot developed by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University‘s Robotics Institute that can discover objects in its surroundings by using more than just computer vision.

The Lifelong Robotic Object Discovery (LROD) process developed by the research team enabled HERB, a two-armed, mobile robot, to use color video, a Kinect depth camera, and non-visual information to discover more than 100 objects in a home-like laboratory.

That allow for finding an objects such as computer monitors, plants and food items, and identifying the objects’ location, size, shape, and even whether they can be lifted.

A robot with initiative

Normally, the CMU researchers build digital models and images of objects and load them into the memory of so the robot can recognize objects that it needs to manipulate. With the team’s implementation of LROD, called HerbDisc, the robot now can discover these objects on its own.

With more time and experience, HerbDisc gradually refines its models of the objects and begins to focus its attention on those that are most relevant to its goal: helping people accomplish tasks of daily living.

The robot’s ability to discover objects on its own sometimes takes even the researchers by surprise, said Siddhartha Srinivasa, associate professor of robotics and head of the Personal Robotics Lab, where HERB is being developed. In one case, some students left the remains of lunch — a pineapple and a bag of bagels — in the lab when they went home for the evening. The next morning, they returned to find that HERB had built digital models of both the pineapple and the bag and had figured out how it could pick up each one.

“We didn’t even know that these objects existed, but HERB did,” said Srinivasa, who jointly supervised the research with Martial Hebert, professor of robotics.

Discovering and understanding objects in places filled with hundreds or thousands of things will be a crucial capability once robots begin working in the home and expanding their role in the workplace. Manually loading digital models of every object of possible relevance simply isn’t feasible, Srinivasa said. “You can’t expect Grandma to do all this,” he added.

Not Object recognition has long been a challenging area of inquiry for computer vision researchers. Recognizing objects based on vision alone quickly becomes an intractable computational problem in a cluttered environment, Srinivasa said. But humans don’t rely on sight alone to understand objects; babies will squeeze a rubber ducky, beat it against the tub, dunk itm even stick it in their mouth. Robots, too, have a lot of “domain knowledge” about their environment that they can use to discover objects.

Depth measurements from HERB’s Kinect sensors proved to be particularly important, Hebert said, providing three-dimensional shape data that is highly discriminative for household items.

Other domain knowledge available to HERB includes location: whether something is on a table, on the floor or in a cupboard. The robot can see whether a potential object moves on its own, or is moveable at all. It can note whether something is in a particular place at a particular time. And it can use its arms to see if it can lift the object, the ultimate test of its “objectness.”

“The first time HERB looks at the video, everything ‘lights up’ as a possible object,” Srinivasa said. But as the robot uses its domain knowledge, it becomes clearer what is and isn’t an object. The team found that adding domain knowledge to the video input almost tripled the number of objects HERB could discover and reduced computer processing time by a factor of 190.

Basic mission: helping people

HERB’s definition of an object — something it can lift — is oriented toward its function as an assistive device for people, doing things such as fetching items or microwaving meals. “It’s a very natural, robot-driven process,” Srinivasa said. “As capabilities and situations change, different things become important.” For instance, HERB can’t yet pick up a sheet of paper, so it ignores paper. But once HERB has hands capable of manipulating paper, it will learn to recognize sheets of paper as objects.

Though not yet implemented, HERB and other robots could use the Internet to create an even richer understanding of objects. Earlier work by Srinivasa showed that robots can use crowdsourcing via Amazon Mechanical Turk to help understand objects. Likewise, a robot might access image sites, such as RoboEarth, ImageNet or 3D Warehouse, to find the name of an object, or to get images of parts of the object it can’t see.

HERB is a project of the Quality of Life Technology Center, a National Science Foundation engineering research center operated by Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh. The center is focused on the development of intelligent systems that improve quality of life for everyone while enabling older adults and people with disabilities.

The Robotics Institute is part of Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science. Follow the school on Twitter @SCSatCMU.