Longevity gene that makes Hydra immortal also controls human aging

November 14, 2012

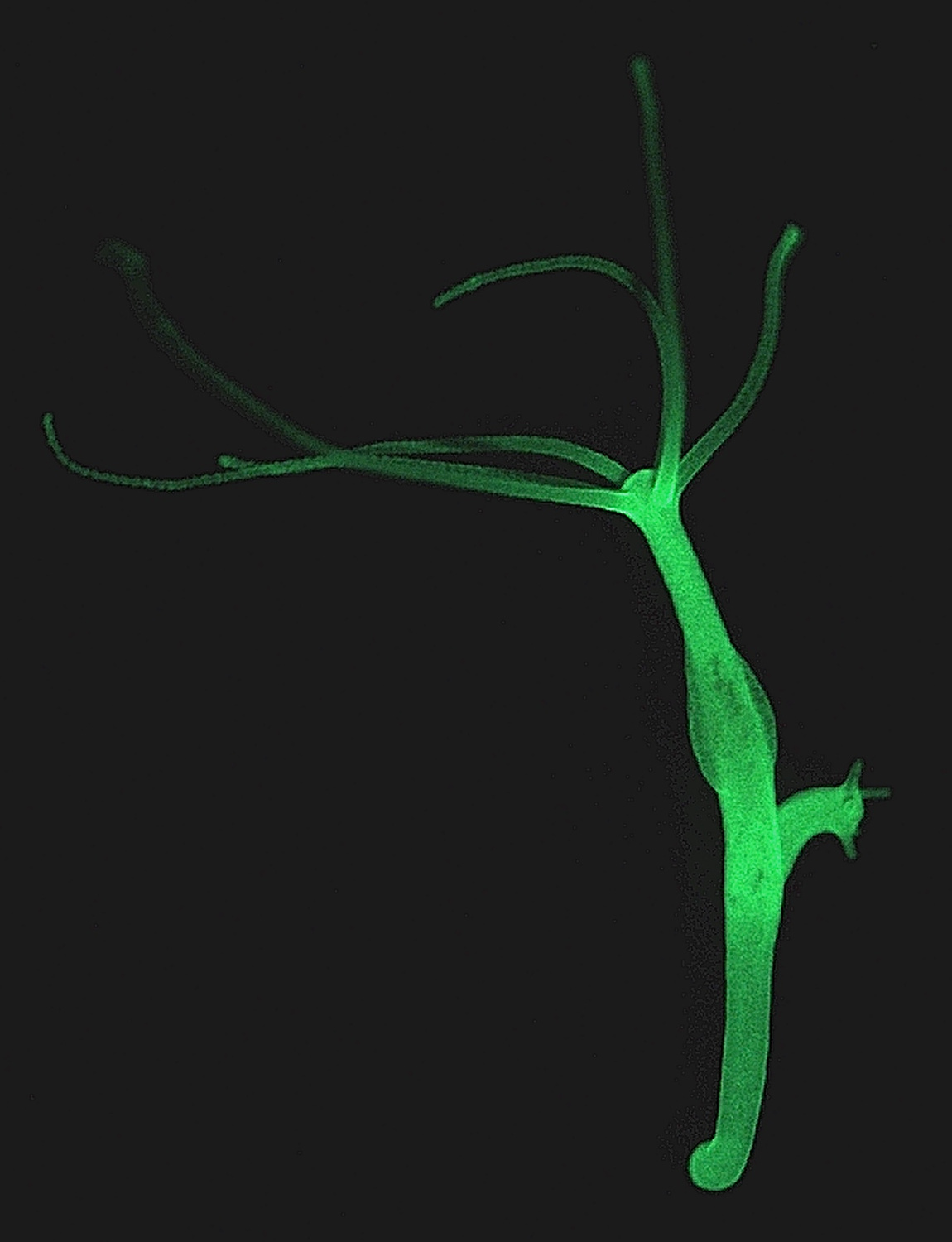

The Hydra polyp reproduces by budding rather than mating. It is about 1 cm in size. Credit: CAU/Fraune)

Why is the polyp Hydra immortal? Researchers from Kiel University decided to study it — and unexpectedly discovered a link to aging in humans.

The study carried out by together with the Keil University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein (UKSH)

The tiny freshwater polyp Hydra does not show any signs of aging and is potentially immortal. There is a rather simple biological explanation for this: these animals exclusively reproduce by budding rather than by mating.

A prerequisite for such vegetative-only reproduction is that each polyp contains stem cells capable of continuous proliferation. Due to its immortality, Hydra has been the subject of many studies regarding aging processes for several years.

When people get older, more and more of their stem cells lose the ability to proliferate and thus to form new cells. Aging tissue cannot regenerate any more, which is why for example muscles decline. Elderly people tend to feel weaker because their heart muscles are affected by this aging process as well.

If it were possible to influence these aging processes, humans could feel physically better for much longer. Studying animal tissue such as those of Hydra — an animal full of active stem cells during all its life — could deliver valuable insight into stem cell aging.

Human longevity gene discovered in Hydra

“Surprisingly, our search for the gene that causes Hydra to be immortal led us to the FoxO gene,“ says Anna-Marei Böhm, PhD student and first author of the study. The FoxO gene exists in all animals and humans and has been known for years. However, until now it was not known why human stem cells become fewer and inactive with increasing age, or which biochemical mechanisms are involved, and whether or not FoxO played a role in aging.

So the research group isolated Hydra’s stem cells and then screened all of their genes. They examined FoxO in several genetically modified polyps: Hydra with normal FoxO, with inactive FoxO, and with enhanced FoxO. The scientists were able to show that animals without FoxO possess significantly fewer stem cells.

Interestingly, the immune system in animals with inactive FoxO also changes drastically. Drastic changes of the immune system similar to those observed in Hydra are also known from elderly humans,“ explains Philip Rosenstiel of the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology at UKSH, whose research group contributed to the study.

“Our research group demonstrated for the first time that there is a direct link between the FoxO gene and aging,“ says Thomas Bosch from the Zoological Institute of Kiel University, who led the Hydra study. “FoxO has been found to be particularly active in centenarians — people older than one hundred years — which is why we believe that FoxO plays a key role in aging — not only in Hydra but also in humans.“

However, the hypothesis cannot be verified on humans, as this would require a genetic manipulation of humans. Bosch stresses however that the current results are still a big step forward in explaining how humans age. The next step will be to study how the longevity gene FoxO works in Hydra, and how environmental factors influence FoxO activity.

The study has two major conclusions: It confirms that the FoxO gene plays a decisive role in the maintenance of stem cells, and thus determines the life span of animals; and it shows that aging and longevity of organisms depend on two factors: the maintenance of stem cells and the maintenance of a functioning immune system.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation DFG.