More-efficient solar-powered steam

July 22, 2014

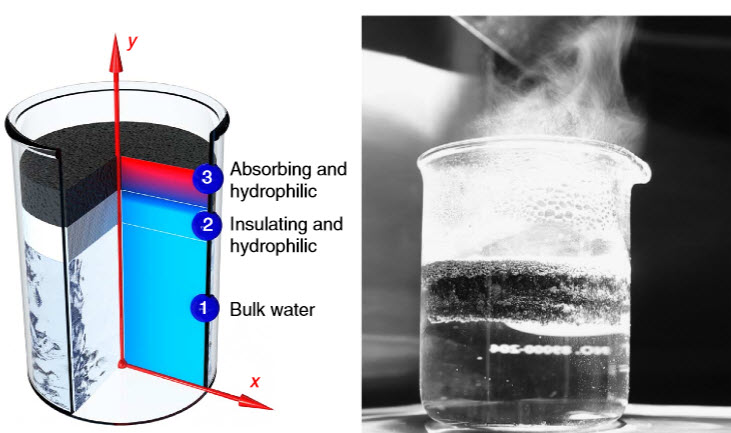

On the left, a representative structure for localization of heat; the cross section of structure and temperature distribution. On the right, a photo of enhanced steam generation by the structure under solar illumination. (Credit: Hadi Ghasemi et al.)

A new carbon-based material structure developed at MIT generates steam from solar energy.

The structure — a layer of graphite flakes and an underlying carbon foam — is a porous, insulating material structure that floats on water.

When sunlight hits the structure’s surface, it creates a hotspot in the graphite, drawing water up through the material’s pores, where it evaporates as steam. The brighter the light, the more steam is generated.

The new material is able to convert 85 percent of incoming solar energy into steam — a significant improvement over recent approaches to solar-powered steam generation. What’s more, the setup loses very little heat in the process, and can produce steam at relatively low solar intensity. This would mean that, if scaled up, the setup would likely not require complex, costly systems to highly concentrate sunlight.

Hadi Ghasemi, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering who led development of the structure, says the spongelike structure can be made from relatively inexpensive materials. “Steam is important for desalination, hygiene systems, and sterilization,” he says . “Especially in remote areas where the sun is the only source of energy, if you can generate steam with solar energy, it would be very useful.”

Ghasemi and mechanical engineering department head Gang Chen, along with five others at MIT, report on the details of the new steam-generating structure in the journal Nature Communications.

Reducing the needed optical concentration

Parabolic trough mirrors used for steam generation in concentrated solar power plants (credit: NOAA)

Today, solar-powered steam generation involves vast fields of mirrors or lenses that concentrate incoming sunlight, heating large volumes of liquid to high enough temperatures to produce steam. These complex systems can experience significant heat loss, leading to inefficient steam generation.

Recently, scientists have explored ways to improve the efficiency of solar-thermal harvesting by developing new solar receivers and by working with nanofluids. The latter approach involves mixing water with nanoparticles that heat up quickly when exposed to sunlight, vaporizing the surrounding water molecules as steam. But initiating this reaction requires very intense solar energy — about 1,000 times that of an average sunny day.

By contrast, the MIT approach generates steam at a solar intensity about 10 times that of a sunny day — the lowest optical concentration reported thus far. The implication, the researchers say, is that steam-generating applications can function with lower sunlight concentration and less-expensive tracking systems.

“This is a huge advantage in cost-reduction,” Ghasemi says. “That’s exciting for us because we’ve come up with a new approach to solar steam generation.”

From sun to steam

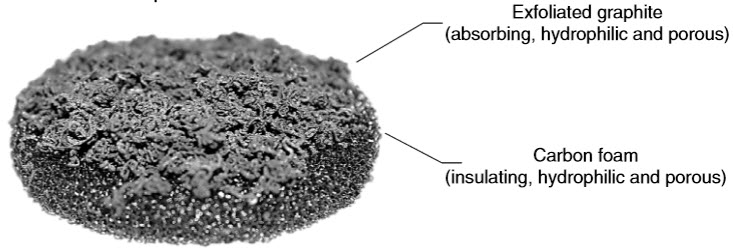

Double-layer structure consists of a carbon foam (10-mm thick)

supporting an exfoliated graphite layer (5-mm thick). Both layers are

hydrophilic (water-seeking) to promote the capillary rise of water to the surface. (Credit: Hadi Ghasemi et al.)

The approach itself is relatively simple: Since steam is generated at the surface of a liquid, Ghasemi looked for a material that could both efficiently absorb sunlight and generate steam at a liquid’s surface.

After trials with multiple materials, he settled on a thin, double-layered, disc-shaped structure. Its top layer is made from graphite that the researchers exfoliated (peeled off) by placing the material in a microwave. The effect, Chen says, is “just like popcorn”: The graphite bubbles up, forming a nest of flakes. The result is a highly porous material that can better absorb and retain solar energy.

The structure’s bottom layer is a carbon foam that contains pockets of air to keep the foam afloat and act as an insulator, preventing heat from escaping to the underlying liquid. The foam also contains very small pores that allow water to creep up through the structure via capillary action.

As sunlight hits the structure, it creates a hotspot in the graphite layer, generating a pressure gradient that draws water up through the carbon foam. As water seeps into the graphite layer, the heat concentrated in the graphite turns the water into steam. The structure works much like a sponge that, when placed in water on a hot, sunny day, can continuously absorb and evaporate liquid.

The researchers tested the structure by placing it in a chamber of water and exposing it to a solar simulator — a light source that simulates various intensities of solar radiation. They found they were able to convert 85 percent of solar energy into steam at a solar intensity 10 times that of a typical sunny day.

Ghasemi says the structure may be designed to be even more efficient, depending on the type of materials used.

“There can be different combinations of materials that can be used in these two layers that can lead to higher efficiencies at lower concentrations,” Ghasemi says. “There is still a lot of research that can be done on implementing this in larger systems.”

Abstract of Nature Communications paper

Currently, steam generation using solar energy is based on heating bulk liquid to high temperatures. This approach requires either costly high optical concentrations leading to heat loss by the hot bulk liquid and heated surfaces or vacuum. New solar receiver concepts such as porous volumetric receivers or nanofluids have been proposed to decrease these losses. Here we report development of an approach and corresponding material structure for solar steam generation while maintaining low optical concentration and keeping the bulk liquid at low temperature with no vacuum. We achieve solar thermal efficiency up to 85% at only 10 kW m−2. This high performance results from four structure characteristics: absorbing in the solar spectrum, thermally insulating, hydrophilic and interconnected pores. The structure concentrates thermal energy and fluid flow where needed for phase change and minimizes dissipated energy. This new structure provides a novel approach to harvesting solar energy for a broad range of phase-change applications.