Nanowire implants for remote-controlled drug delivery

June 25, 2015

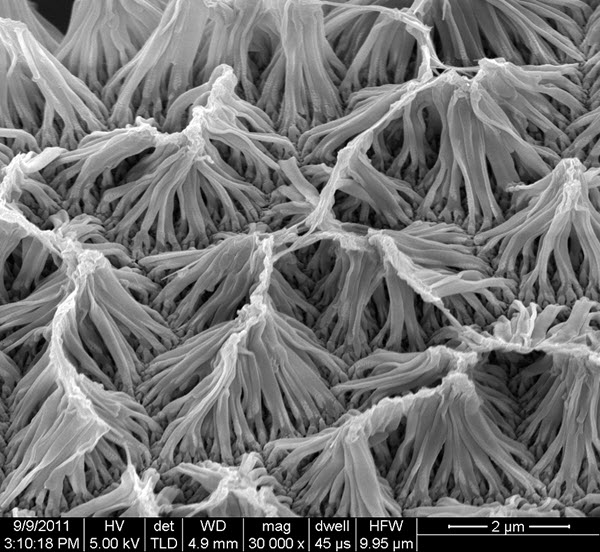

An image of a field of polypyrrole nanowires captured by a scanning electron microscope is shown. A team of Purdue University researchers developed a new implantable drug-delivery system using the nanowires, which can be wirelessly controlled to release small amounts of a drug payload. (credit: Richard Borgens/Purdue University)

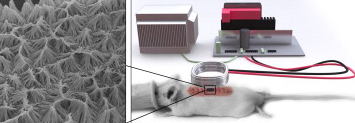

Purdue researchers have created a new implantable drug-delivery system using nanowires that can be wirelessly controlled. The nanowires respond to an electromagnetic field generated by a separate device, which can be used to control the release of a preloaded drug.

The system eliminates the tubes and wires required by other implantable devices that can lead to infection and other complications, said team leader Richard Borgens, Purdue University’s Mari Hulman George Professor of Applied Neuroscience and director of Purdue’s Center for Paralysis Research.

“This tool allows us to apply drugs as needed directly to the site of injury, which could have broad medical applications,” Borgens said. “The technology is in the early stages of testing, but it is our hope that this could one day be used to deliver drugs directly to spinal cord injuries, ulcerations, deep bone injuries or tumors, and avoid the terrible side effects of systemic treatment with steroids or chemotherapy.”

The team tested the drug-delivery system in mice with compression injuries to their spinal cords and administered the corticosteroid dexamethasone. The study measured a molecular marker of inflammation and scar formation in the central nervous system and found that it was reduced after one week of treatment.

Polypyrrole nanowires

The electromagnetic drug-delivery system (credit: Richard Borgens/Purdue University)

Wen Gao, a postdoctoral researcher in the Center for Paralysis Research who worked on the project with Borgens, grew the nanowires vertically over a thin gold base, like tiny fibers making up a piece of shag carpet hundreds of times smaller than a human cell.

The nanowires are made of polypyrrole, a conductive polymer material that responds to electromagnetic fields. They were loaded with a drug and exposed to an approximately 25–40 Gauss pulsed magnetic field with 3000–5000 V/m electrical field at the injury sites for 2 hours daily, causing the nanowires to release small amounts of the payload. This process can be started and stopped at will, like flipping a switch, Borgens said.

As KurzweilAI reported earlier this month, polypyrrole nanowires were also used by ETH Zurich and Technion researchers in an elastic “nanoswimmer” that can move through biological fluid environments to deliver drugs, also controlled by a pulsed magnetic field.

The magnitude and wave form of the pulsed magnetic field must be tuned to obtain the optimum release of the drug, and the precise mechanisms that release the drug are not yet well understood, Borgens said.

“We think it is a combination of charge effects and the shape change of the polymer that allows it to store and release drugs,” he said. “It is a reversible process. Once the electromagnetic field is removed, the polymer snaps back to the initial architecture and retains the remaining drug molecules.” For each different drug the team would need to find the corresponding optimal electromagnetic field for its release.

Testing drug-delivery in mice

The team used mice that had been genetically modified such that the protein Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein, or GFAP, is luminescent. GFAP is expressed in cells called astrocytes that gather in high numbers at central nervous system injuries. Astrocytes are a part of the inflammatory process and form scar tissue, Borgens said.

A 1–2 millimeter patch of the nanowires doped with dexamethasone was placed onto spinal cord lesions that had been surgically exposed, Borgens said. The lesions were then closed and an electromagnetic field was applied for two hours a day for one week. By the end of the week the treated mice had a weaker GFAP signal than the control groups, which included mice that were not treated and those that received a nanowire patch but were not exposed to the electromagnetic field. In some cases, treated mice had no detectable GFAP signal.

Whether the reduction in astrocytes had any significant impact on spinal cord healing or functional outcomes was not studied. In addition, the concentration of drug maintained during treatment is not known because it is below the limits of systemic detection, Borgens said.

“This method allows a very, very small dose of a drug to effectively serve as a big dose right where you need it,” Borgens said. “By the time the drug diffuses from the site out into the rest of the body it is in amounts that are undetectable in the usual tests to monitor the concentration of drugs in the bloodstream.”

Polypyrrole is an inert and biocompatable material, but the team is working to create a biodegradeable form that would dissolve after the treatment period ended. The team also is trying to increase the depth at which the drug delivery device will work. The current system appears to be limited to a depth in tissue of less than 3 centimeters, Gao said.

The research is described in an online open-access paper in the Journal of Controlled Release.

The research was funded through the general funds of the Center for Paralysis Research and an endowment from Mrs. Mari Hulman George. Borgens has a dual appointment in Purdue’s College of Engineering and the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Abstract of Remote-controlled eradication of astrogliosis in spinal cord injury via electromagnetically-induced dexamethasone release from “smart” nanowires

We describe a system to deliver drugs to selected tissues continuously, if required, for weeks. Drugs can be released remotely inside the small animals using pre-implanted, novel vertically aligned electromagnetically-sensitive polypyrrole nanowires (PpyNWs). Approximately 1–2 mm2 dexamethasone (DEX) doped PpyNWs was lifted on a single drop of sterile water by surface tension, and deposited onto a spinal cord lesion in glial fibrillary acidic protein-luc transgenic mice (GFAP-luc mice). Overexpression of GFAP is an indicator of astrogliosis/neuroinflammation in CNS injury. The corticosteroid DEX, a powerful ameliorator of inflammation, was released from the polymer by external application of an electromagnetic field for 2 h/day for a week. The GFAP signal, revealed by bioluminescent imaging in the living animal, was significantly reduced in treated animals. At 1 week, GFAP was at the edge of detection, and in some experimental animals, completely eradicated. We conclude that the administration of drugs can be controlled locally and non-invasively, opening the door to many other known therapies, such as the cases that dexamethasone cannot be safely applied systemically in large concentrations.