New type of retinal prosthesis could restore sight to blind

May 14, 2012

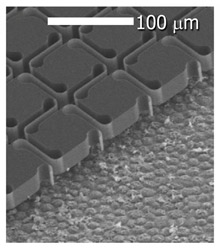

A photovoltaic retinal prosthesis --- a flexible sheet of silicon pixels that convert light into electrical signals that can be picked up by neurons in the eye. A scanning-electron micrograph shows the implant in a pig’s eye. (Credit: Nature Photonics/Stanford)

Using tiny solar-panel-like cells surgically placed underneath the retina, scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine have devised a system that may someday restore sight to people who have lost vision because of certain types of degenerative eye diseases.

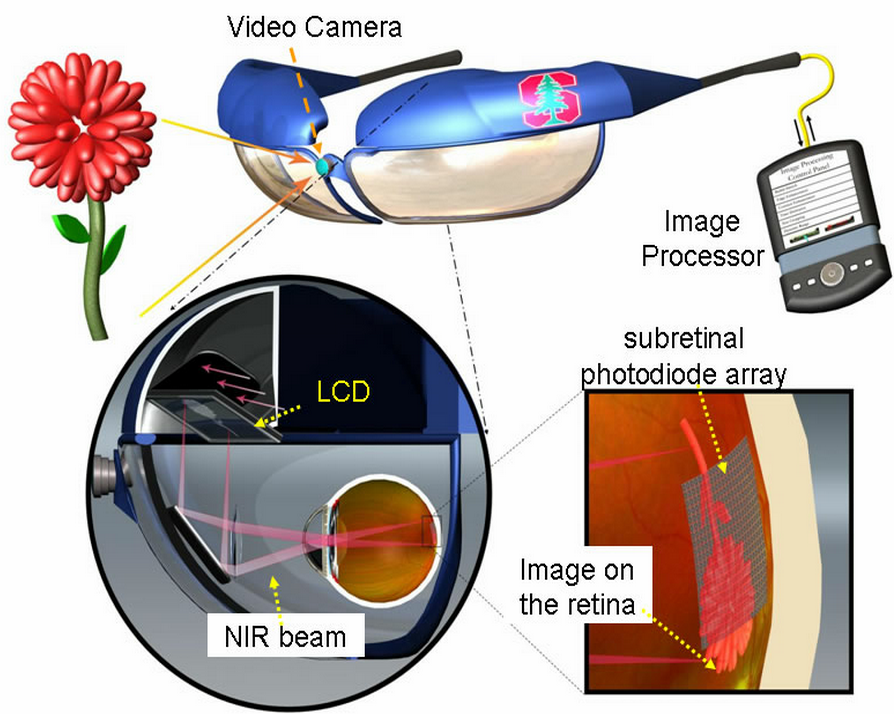

This device — a new type of retinal prosthesis — involves a specially designed pair of goggles, which are equipped with a miniature camera and a pocket PC designed to process the visual data stream. The resulting images would be displayed on a liquid crystal microdisplay embedded in the goggles, similar to what’s used in video goggles for gaming, corresponding to approximately 30 degrees of visual field .

Unlike the regular video goggles, though, the images would be beamed from the LCD using laser pulses of near-infrared light to a photovoltaic array on a silicon chip — one-third as thin as a strand of hair — implanted beneath the retina. It would have 25 micron (millionths of a meter, about 1/1000th of an inch) pixels, each containing a ~10 micron stimulating electrode.

Electric currents from the photodiodes on the chip would then trigger signals in the retina, which then flow to the brain, enabling a patient to regain vision.

The retinal chip is approximately 3 mm in diameter, corresponding to 10 degrees of visual field. The 30 degree visual field is accessible by eye scanning.

A portable computer processes video images captured by a head-mounted camera. Video goggles then project these images onto the retina using pulsed infrared (880–915 nm) illumination. Electric currents from the photodiodes on the chip then trigger signals in the retina that then flow to the brain, enabling a patient to regain vision. (Credit: K. Mathieson et al./Keith Mathieson et al./Nature Photonics)

Scientists tested the photovoltaic stimulation using the prosthetic device’s diode arrays in rat retinas in vitro and how they elicited electric responses, which are widely accepted indicators of visual activity, from retinal cells . The scientists are now testing the system in live rats, taking both physiological and behavioral measurements, and are hoping to find a sponsor to support tests in humans.

There are several other retinal prostheses being developed, and at least two of them are in clinical trials. A device made by the Los Angeles-based company Second Sight was approved in April for use in Europe, and another prosthesis-maker, a German company called Retina Implant AG, announced earlier this month results from its clinical testing in Europe.

Unlike these other devices — which require coils, cables or antennas inside the eye to deliver power and information to the retinal implant — the Stanford device uses near-infrared light to transmit images, thereby avoiding any need for wires and cables, and making the device thin and easily implantable.

“The current implants are very bulky, and the surgery to place the intraocular wiring for receiving, processing and power is difficult,” said Daniel Palanker, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology. The device developed by his team, he noted, has virtually all of the hardware incorporated externally into the goggles. “The surgeon needs only to create a small pocket beneath the retina and then slip the photovoltaic cells inside it.” What’s more, one can tile these photovoltaic cells in larger numbers inside the eye to provide a wider field of view than the other systems can offer, he added.

The current design allows for 178 pixels per square millimeter. By comparison, the first retinal prosthesis to go to market, made by Second Sight of Sylmar, California, has 60 pixels in total and requires bulkier hardware.

However, thousands of pixels are likely to be required for functional restoration of sight, such as reading and face recognition, Palanker said on his Stanford page.

Conceptual diagram of the photovoltaic pixels with pillar electrodes (1) penetrating into the inner nuclear layer. The return electrodes (2) are located in the plane of the photodiodes. (Credit: Daniel Palanker)

Stanford University holds patents on two technologies used in the system, and Palanker and colleagues would receive royalties from the licensing of these patents.

Clinical trials are expected in a few years.

A prosthesis for retinal degenerative diseases

The proposed prosthesis is intended to help people suffering from retinal degenerative diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa. The former is the foremost cause of vision loss in North America, and the latter causes an estimated 1.5 million people worldwide to lose sight, according to the nonprofit group Foundation Fighting Blindness.

In these diseases, the retina’s photoreceptor cells slowly degenerate, ultimately leading to blindness. But the inner retinal neurons that normally transmit signals from the photoreceptors to the brain are largely unscathed. Retinal prostheses are based on the idea that there are other ways to stimulate those neurons.

The Stanford device uses near-infrared light, which has longer wavelength than normal visible light. It’s necessary to use such an approach because people blinded by retinal degenerative diseases still have photoreceptor cells, which continue to be sensitive to visible light. “To make this work, we have to deliver a lot more light than normal vision would require,” said Palanker. “And if we used visible light, it would be painfully bright.” Near-infrared light isn’t visible to the naked eye, though it is “visible” to the diodes that are implanted as part of this prosthetic system, he said.

For this study, Palanker and his team fabricated a chip about the size of a pencil point that contains hundreds of these light-sensitive diodes. To test how these chips responded, the researchers used retinas from both normal rats and blind rats that serve as models of retinal degenerative disease. The scientists placed an array of photodiodes beneath the retinas and placed a multi-electrode array above the layer of ganglion cells to gauge their activity. The scientists then sent pulses of light, both visible and near-infrared, to produce electric current in the photodiodes and measured the response in the outer layer of the retinas.

In the normal rats, the ganglions were stimulated, as expected, by the normal visible light, but they also presented a similar response to the near-infrared light: That’s confirmation that the diodes were triggering neural activity.

In the degenerative rat retinas, the normal light elicited little response, but the near-infrared light prompted strong spikes in activity roughly similar to what occurred in the normal rat retinas. “They didn’t respond to normal light, but they did to infrared,” said Palanker. “This way the sight is restored with our system.” He noted that the degenerated rat retinas required greater amounts of near-infrared light to achieve the same level of activity as the normal rat retinas.

While there was concern that exposure to such doses of near-infrared light could cause the tissue to heat up, the study found that the irradiation was still one-hundredth of the established ocular safety limit.

Since completing the study, Palanker and his colleagues have implanted the photodiodes in rats’ eyes and been observing and measuring their effect for the last six months. He said preliminary data indicates that the visual signals are reaching the brain in normal and in blind rats, though the study is still under way.

While this and other devices could help people to regain some sight, the current technologies do not allow people to see color, and the resulting vision is far from normal, Palanker said.

Ref.: Keith Mathieson et al., Photovoltaic retinal prosthesis with high pixel density, Nature Photonics, 2012, DOI: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.104