People with paralysis control robotic arms using brain-computer interface

May 17, 2012

(Credit: Brown University)

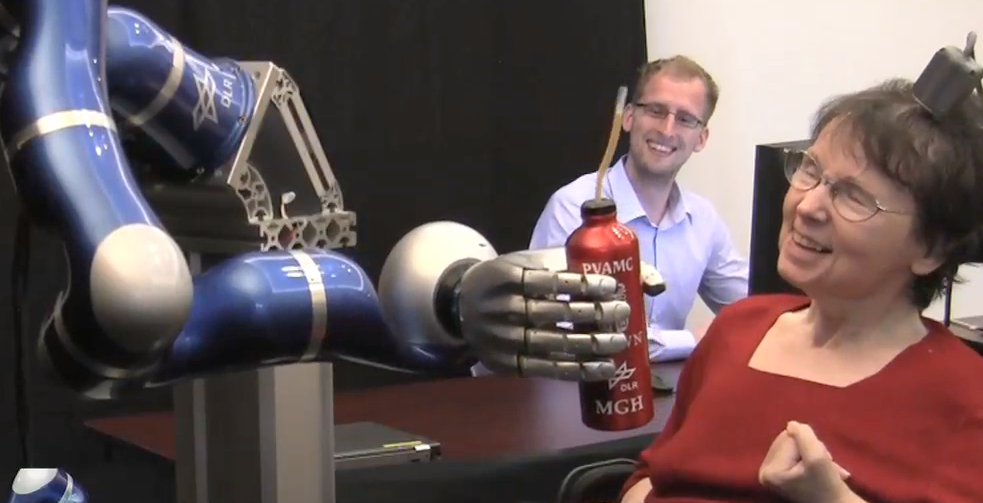

On April 12, 2011, nearly 15 years after she became paralyzed and unable to speak, a woman controlled a robotic arm by thinking about moving her arm and hand to lift a bottle of coffee to her mouth and take a drink, using the BrainGate neural interface system.

That achievement is one of the advances in brain-computer interfaces, restorative neurotechnology, and assistive robot technology by the BrainGate2 collaboration of researchers at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Brown University, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

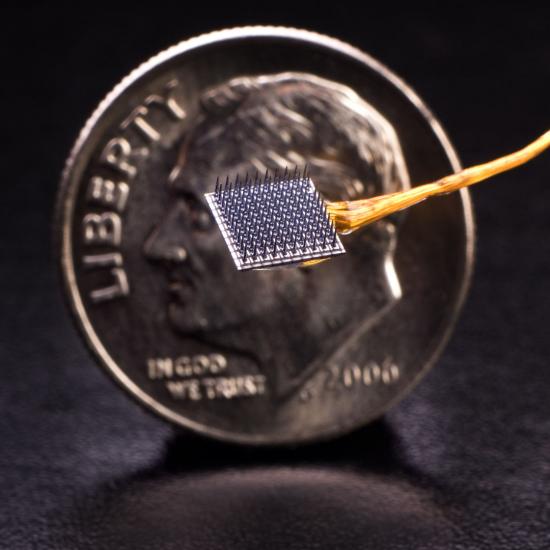

The BrainGate2 Neural Interface System: an implanted microelectrode array detects brain signals, which are converted by a computer into machine instructions, allowing control of robotic devices by thought (credit: Brown University)

A 58-year-old woman and a 66-year-old man participated in the study. They had each been paralyzed by a brainstem stroke years earlier, which left them with no functional control of their limbs.

In the research, the participants used neural activity to directly control two different robotic arms, one developed by the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics and the other by DEKA Research and Development Corp., to perform reaching and grasping tasks across a broad three-dimensional space.

The BrainGate2 pilot clinical trial employs the investigational BrainGate system initially developed at Brown University, in which a baby aspirin-sized device with a grid of 96 tiny electrodes is implanted in the motor cortex — a part of the brain that is involved in voluntary movement.

The electrodes are close enough to individual neurons to record the neural activity associated with intended movement. An external computer translates the pattern of impulses across a population of neurons into commands to operate assistive devices, such as the DLR and DEKA robot arms used in the study.

BrainGate participants have previously demonstrated neurally based two-dimensional point-and-click control of a cursor on a computer screen and rudimentary control of simple robotic devices.

The study represents the first demonstration and the first peer-reviewed report of people with tetraplegia using brain signals to control a robotic arm in three-dimensional space to complete a task usually performed by their arm.

“Our goal in this research is to develop technology that will restore independence and mobility for people with paralysis or limb loss,” said lead author Dr. Leigh Hochberg, a neuroengineer and critical care neurologist who holds appointments at the Department of Veterans Affairs, Brown University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard.

Hochberg adds that even after nearly 15 years, a part of the brain essentially “disconnected” from its original target by a brainstem stroke was still able to direct the complex, multidimensional movement of an external arm — in this case, a robotic limb. The researchers also noted that one patient was able to perform the tasks more than five years after the investigational BrainGate electrode array was implanted. This sets a new benchmark for how long implanted brain-computer interface electrodes have remained viable and provided useful command signals.

John Donoghue, the VA and Brown neuroscientist who pioneered BrainGate more than a decade ago and who is co-senior author of the study, said the paper shows how far the field of brain-computer interfaces has come since the first demonstrations of computer control with BrainGate.

“This paper reports an important advance by rigorously demonstrating in more than one participant that precise three-dimensional neural control of robot arms is not only possible, but also repeatable,” said Donoghue, who directs the Brown Institute for Brain Science.

“We’ve moved significantly closer to returning everyday functions, like serving yourself a sip of coffee, usually performed effortlessly by the arm and hand, for people who are unable to move their own limbs. We are also encouraged to see useful control more than five years after implant of the BrainGate array in one of our participants. This work is a critical step toward realizing the long-term goal of creating a neurotechnology that will restore movement, control, and independence to people with paralysis or limb loss.”

In the research, the robots acted as a substitute for each participant’s paralyzed arm. The robotic arms responded to the participants’ intent to move as they imagined reaching for each foam target. The robot hand grasped the target when the participants imagined a hand squeeze. Because the diameter of the targets was more than half the width of the robot hand openings, the task required the participants to exert precise control.

In 158 trials over four days, subject S3 was able to touch the target within an allotted time in 48.8 percent of the cases using the DLR robotic arm and hand and 69.2 percent of the cases with the DEKA arm and hand, which has the wider grasp. In 45 trials using the DEKA arm, T2 touched the target 95.6 percent of the time. Of the successful touches, S3 grasped the target 43.6 percent of the time with the DLR arm and 66.7 percent of the time with the DEKA arm. T2’s grasp succeeded 62.2 percent of the time.

T2 performed the session in this study on his fourth day of interacting with the arm; the prior three sessions were focused on system development. Using his eyes to indicate each letter, he later described his control of the arm: “I just imagined moving my own arm and the [DEKA] arm moved where I wanted it to go.”

The study used two advanced robotic arms: the DLR Light-Weight Robot III with DLR five-fingered hand and the DEKA Arm System. The DLR LWR-III, which is designed to assist in recreating actions like the human arm and hand and to interact with human users, could be valuable as an assistive robotic device for people with various disabilities.

Patrick van der Smagt, head of bionics and assistive robotics at DLR, director of biomimetic robotics and machine learning labs at DLR and the Technische Universität München, and a co-senior author on the paper said: “This is what we were hoping for with this arm. We wanted to create an arm that could be used intuitively by varying forms of control. The arm is already in use by numerous research labs around the world who use its unique interaction and safety capabilities. This is a compelling demonstration of the potential utility of the arm by a person with paralysis.”

DEKA Research and Development developed the DEKA Arm System for amputees, through funding from the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Dean Kamen, founder of DEKA said, “One of our dreams for the Luke Arm [as the DEKA Arm System is known informally] since its inception has been to provide a limb that could be operated not only by external sensors, but also by more directly thought-driven control.

“We’re pleased about these results and for the continued research being done by the group at the VA, Brown and MGH.” The research is aimed at learning how the DEKA arm might be controlled directly from the brain, potentially allowing amputees to more naturally control this prosthetic limb.

Over the last two years, VA has been conducting an optimization study of the DEKA prosthetic arm at several sites, with the cooperation of veterans and active duty service members who have lost an arm. Feedback from the study is helping DEKA engineers to refine the artificial arm’s design and function. “Brain-computer interfaces, such as BrainGate, have the potential to provide an unprecedented level of functional control over prosthetic arms of the future,” said Joel Kupersmith, M.D., VA chief research and development officer. “This innovation is an example of federal collaboration at its finest.”

Story Landis, director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which funded the work in part, noted: “This technology was made possible by decades of investment and research into how the brain controls movement. It’s been thrilling to see the technology evolve from studies of basic neurophysiology and move into clinical trials, where it is showing significant promise for people with brain injuries and disorders.”

Ref.: Leigh R. Hochberg et al., Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm, Nature, 2012, DOI: 10.1038/nature11076

(Additional videos available on the Nature website)