Slowing down the aging process by ‘remote control’

September 10, 2014

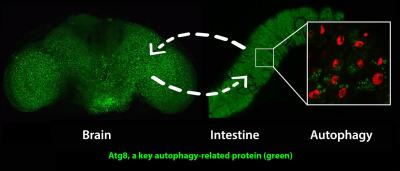

Activating a gene called AMPK in the nervous system induces the anti-aging cellular recycling process of autophagy in both the brain and intestine. Activating AMPK in the intestine leads to increased autophagy in both the intestine and brain. Matthew Ulgherait, David Walker and UCLA colleagues showed that this ‘inter-organ’ communication during aging can substantially prolong the healthy lifespan of fruit flies. (Credit: Matthew Ulgherait/UCLA)

UCLA biologists have identified a gene that can slow the aging process throughout the entire body when activated remotely in key organ systems.

Working with fruit flies, the life scientists activated a gene called AMPK that is a key energy sensor in cells; it gets activated when cellular energy levels are low.

Increasing the amount of AMPK in fruit flies’ intestines increased their lifespans by about 30 percent — to roughly eight weeks from the typical six — and the flies stayed healthier longer as well.

The research, published Sept. 4 in the open-source journal Cell Reports, could have important implications for delaying aging and disease in humans, said David Walker, an associate professor of integrative biology and physiology at UCLA and senior author of the research.

“We have shown that when we activate the [AMPK] gene in the intestine or the nervous system, we see the aging process is slowed beyond the organ system in which the gene is activated,” Walker said.

Walker said that the findings are important because extending the healthy life of humans would presumably require protecting many of the body’s organ systems from the ravages of aging — but delivering anti-aging treatments to the brain or other key organs could prove technically difficult. The study suggests that activating AMPK in a more accessible organ such as the intestine, for example, could ultimately slow the aging process throughout the entire body, including the brain.

Humans have AMPK, but it is usually not activated at a high level, Walker said.

“Instead of studying the diseases of aging — Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, stroke, cardiovascular disease, diabetes — one by one, we believe it may be possible to intervene in the aging process and delay the onset of many of these diseases,” said Walker, a member of UCLA’s Molecular Biology Institute. “We are not there yet, and it could, of course, take many years, but that is our goal and we think it is realistic.

“The ultimate aim of our research is to promote healthy aging in people.”

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is a good model for studying aging in humans because scientists have identified all of the fruit fly’s genes and know how to switch individual genes on and off. The biologists studied approximately 100,000 of them over the course of the study.

Lead author Matthew Ulgherait, who conducted the research in Walker’s laboratory as a doctoral student, focused on a cellular process called autophagy, which enables cells to degrade and discard old, damaged cellular components. By getting rid of that “cellular garbage” before it damages cells, autophagy protects against aging, and AMPK has been shown previously to activate this process.

Ulgherait studied whether activating AMPK in the flies led to autophagy occurring at a greater rate than usual.

“A really interesting finding was when Matt activated AMPK in the nervous system, he saw evidence of increased levels of autophagy in not only the brain, but also in the intestine,” said Walker, a faculty member in the UCLA College. “And vice versa: Activating AMPK in the intestine produced increased levels of autophagy in the brain — and perhaps elsewhere, too.”

Many neurodegenerative diseases, including both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, are associated with the accumulation of protein aggregates, a type of cellular garbage, in the brain, Walker noted.

“Matt moved beyond correlation and established causality,” he said. “He showed that the activation of autophagy was both necessary to see the anti-aging effects and sufficient; that he could bypass AMPK and directly target autophagy.”

Walker said that AMPK is thought to be a key target of metformin, a drug used to treat Type 2 diabetes, and that metformin activates AMPK.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging. Ulgherait received funding support from a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award and Eureka and Hyde fellowships from the UCLA department of integrative biology and physiology.

Abstract of Cell Reports paper

- Neuronal AMPK induces autophagy in brain and gut and slows systemic aging

- Neuronal Atg1 induces autophagy in brain and gut and slows systemic aging

- Intestinal AMPK induces autophagy in gut and brain and slows systemic aging

- Intertissue effects of AMPK/Atg1 linked to altered insulin-like signaling

AMPK exerts prolongevity effects in diverse species; however, the tissue-specific mechanisms involved are poorly understood. Here, we show that upregulation of AMPK in the adult Drosophila nervous system induces autophagy both in the brain and also in the intestinal epithelium. Induction of autophagy is linked to improved intestinal homeostasis during aging and extended lifespan. Neuronal upregulation of the autophagy-specific protein kinase Atg1 is both necessary and sufficient to induce these intertissue effects during aging and to prolong the lifespan. Furthermore, upregulation of AMPK in the adult intestine induces autophagy both cell autonomously and non-cell-autonomously in the brain, slows systemic aging, and prolongs the lifespan. We show that the organism-wide response to tissue-specific AMPK/Atg1 activation is linked to reduced insulin-like peptide levels in the brain and a systemic increase in 4E-BP expression. Together, these results reveal that localized activation of AMPK and/or Atg1 in key tissues can slow aging in a non-cell-autonomous manner.