Special polymer gel allows adult-stem-cell differentiation without immune rejection

May 25, 2012

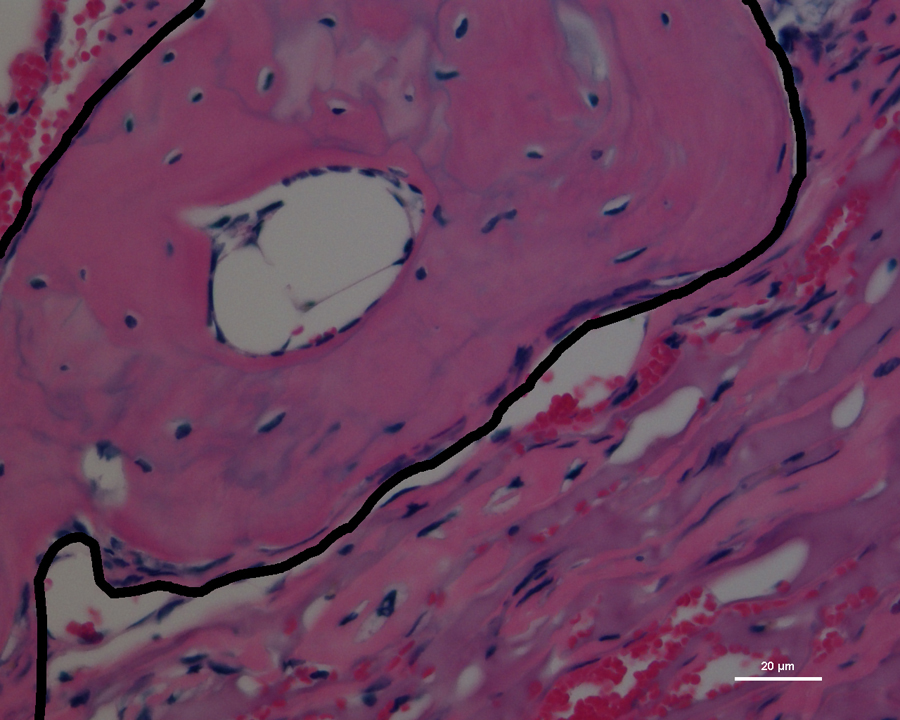

The black outline partially encloses the new bone growth in the skull of the mouse, stained pink for imaging (credit: Villa-Diaz, L.G. et al./University of Michigan)

University of Michigan researchers have proven that a special surface, free of biological contaminants, allows adult-derived stem cells to thrive and transform into multiple cell types.

Their success brings stem cell therapies another step closer. To prove the cells’ regenerative powers, bone cells grown on this surface were then transplanted into holes in the skulls of mice, producing four times as much new bone growth as in the mice without the extra bone cells.

An embryo’s cells really can be anything they want to be when they grow up: organs, nerves, skin, bone, any type of human cell. Adult-derived “induced” stem cells can do this and better. Because the source cells can come from the patient, they are perfectly compatible for medical treatments.

In order to make them, “We turn back the clock, in a way,” said Paul Krebsbach, a professor of biological and materials sciences in the School of Dentistry. “We’re taking a specialized adult cell and genetically reprogramming it, so it behaves like a more primitive cell.”

Specifically, they turn human skin cells into stem cells. Less than five years after the discovery of this method, researchers still don’t know precisely how it works, but the process involves adding proteins that can turn genes on and off to the adult cells.

Before stem cells can be used to make repairs in the body, they must be grown and differentiated, that is, directed into becoming the desired cell type. Researchers typically use surfaces of animal cells and proteins for stem cell habitats, but these gels are expensive to make, and batches vary depending on the individual animal.

“You don’t really know what’s in there,” said Joerg Lahann, an associate professor of chemical engineering and biomedical engineering. For example, human cells are often grown over mouse cells, but they can go a little native, beginning to produce some mouse proteins that may invite an attack by a patient’s immune system.

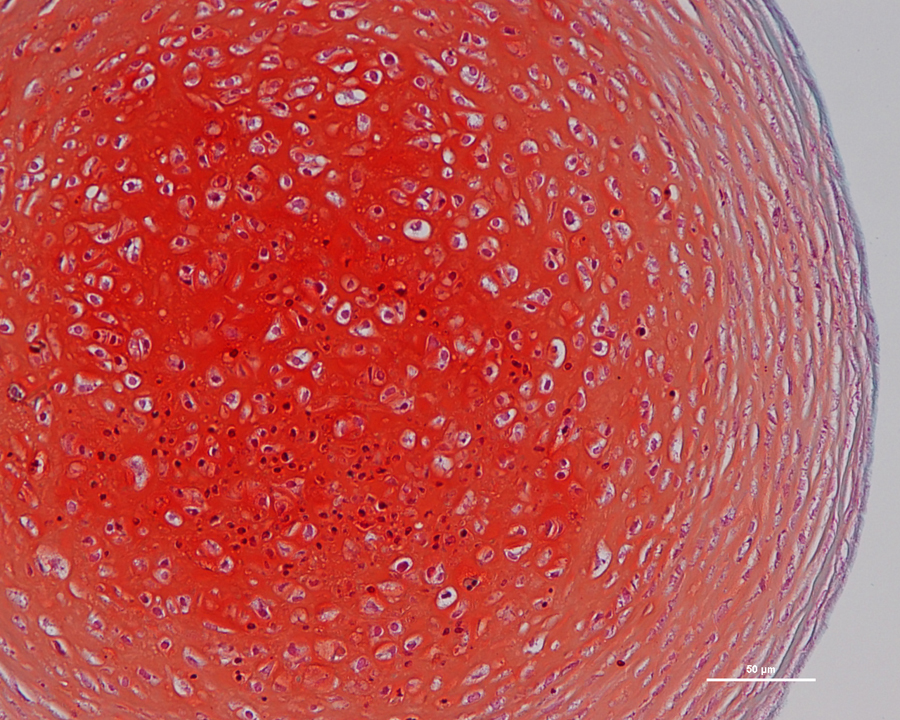

Induced stem cells have been turned into cartilage cells on the contaminant-free surface (credit: Villa-Diaz, L.G. et al./University of Michigan)

Controlled ingredients avoid immune rejection

The polymer gel created by Lahann and his colleagues in 2010 avoids these problems because researchers are able to control all of the gel’s ingredients and how they combine. “It’s basically the ease of a plastic dish,” said Lahann. “There is no biological contamination that could potentially influence your human stem cells.”

Lahann and colleagues had shown that these surfaces could grow embryonic stem cells. Now, Lahann has teamed up with Krebsbach’s team to show that the polymer surface can also support the growth of the more medically promising induced stem cells, keeping them in their high-potential state. To prove that the cells could transform into different types, the team turned them into fat, cartilage, and bone cells.

They then tested whether these cells could help the body to make repairs. Specifically, they attempted to repair 5-millimeter holes in the skulls of mice. The weak immune systems of the mice didn’t attack the human bone cells, allowing the cells to help fill in the hole.

After eight weeks, the mice that had received the bone cells had 4.2 times as much new bone, as well as the beginnings of marrow cavities. The team could prove that the extra bone growth came from the added cells because it was human bone.

“The concept is not specific to bone,” said Krebsbach. “If we truly develop ways to grow these cells without mouse or animal products, eventually other scientists around the world could generate their tissue of interest.”

In the future, Lahann’s team wants to explore using their gel to grow stem cells and specialized cells in different physical shapes, such as a bone-like structure or a nerve-like microfiber.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Ref.: L.G. Villa-Diaz et al., Derivation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Cultured on Synthetic Substrates, Stem Cells, 2012, DOI: 10.1002/stem.1084

See also: Turning off the stem-cell aging switch