Speech-classifier program is better at predicting psychosis than psychiatrists

August 31, 2015

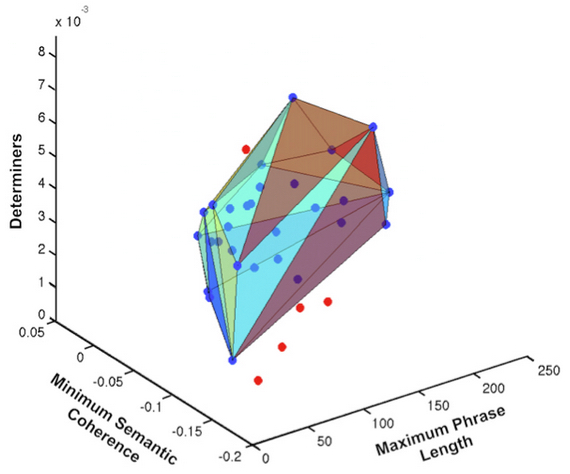

This image shows discrimination between at-risk youths who transitioned to psychosis (red) and those who did not (blue). The polyhedron contains all the at-risk youth who did NOT develop psychosis (blue). All of the at-risk youth who DID later develop psychosis (red) are outside the polyhedron. Thus the speech classifier had 100 percent discrimination or accuracy. The speech classifier consisted of “minimum semantic coherence” (the flow of meaning from one sentence to the next), and indices of reduced complexity of speech, including phrase length and decreased use of “determiner” pronouns (“that,” “what,” “whatever,” “which,” and “whichever”). (credit: Cheryl Corcoran et al./NPJ Schizophrenia/Columbia University Medical Center)

An automated speech analysis program correctly differentiated between at-risk young people who developed psychosis over a later two-and-a-half year period and those who did not.

In a proof-of-principle study, researchers at Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center found that the computerized analysis provided a more accurate classification than clinical ratings. The study was published Wednesday Aug. 26 in an open-access paper in NPJ-Schizophrenia.

About one percent of the population between the ages of 14 and 27 is considered to be at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis. CHR individuals have symptoms such as unusual or tangential thinking, perceptual changes, and suspiciousness. About 20% will go on to experience a full-blown psychotic episode. Identifying who falls in that 20% category before psychosis occurs has been an elusive goal. Early identification could lead to intervention and support that could delay, mitigate or even prevent the onset of serious mental illness.

Measuring psychosis

Speech provides a unique window into the mind, giving important clues about what people are thinking and feeling. Participants in the study took part in an open-ended, narrative interview in which they described their subjective experiences. These interviews were transcribed and then analyzed by computer for patterns of speech, including semantics (meaning) and syntax (structure).

The analysis established each patient’s semantic coherence (how well he or she stayed on topic), and syntactic structure, such as phrase length and use of determiner words that link the phrases. A clinical psychiatrist may intuitively recognize these signs of disorganized thoughts in a traditional interview, but a machine can augment what is heard by precisely measuring the variables. The participants were then followed for two and a half years.

The speech features that predicted psychosis onset included breaks in the flow of meaning from one sentence to the next, and speech that was characterized by shorter phrases with less elaboration.

Speech classifier: 100% accurate

The speech classifier tool developed in this study to mechanically sort these specific, symptom-related features is striking for achieving 100% accuracy. The computer analysis correctly differentiated between the five individuals who later experienced a psychotic episode and the 29 who did not.

These results suggest that this method may be able to identify thought disorder in its earliest, most subtle form, years before the onset of psychosis. Thought disorder is a key component of schizophrenia, but quantifying it has proved difficult.

For the field of schizophrenia research, and for psychiatry more broadly, this opens the possibility that new technology can aid in prognosis and diagnosis of severe mental disorders, and track treatment response. Automated speech analysis is inexpensive, portable, fast, and non-invasive. It has the potential to be a powerful tool that can complement clinical interviews and ratings.

Further research with a second, larger group of at-risk individuals is needed to see if this automated capacity to predict psychosis onset is both robust and reliable. Automated speech analysis used in conjunction with neuroimaging may also be useful in reaching a better understanding of early thought disorder, and the paths to develop treatments for it.

Abstract of Automated analysis of free speech predicts psychosis onset in high-risk youths

Background/Objectives: Psychiatry lacks the objective clinical tests routinely used in other specializations. Novel computerized methods to characterize complex behaviors such as speech could be used to identify and predict psychiatric illness in individuals.

AIMS: In this proof-of-principle study, our aim was to test automated speech analyses combined with Machine Learning to predict later psychosis onset in youths at clinical high-risk (CHR) for psychosis.

Methods: Thirty-four CHR youths (11 females) had baseline interviews and were assessed quarterly for up to 2.5 years; five transitioned to psychosis. Using automated analysis, transcripts of interviews were evaluated for semantic and syntactic features predicting later psychosis onset. Speech features were fed into a convex hull classification algorithm with leave-one-subject-out cross-validation to assess their predictive value for psychosis outcome. The canonical correlation between the speech features and prodromal symptom ratings was computed.

Results: Derived speech features included a Latent Semantic Analysis measure of semantic coherence and two syntactic markers of speech complexity: maximum phrase length and use of determiners (e.g., which). These speech features predicted later psychosis development with 100% accuracy, outperforming classification from clinical interviews. Speech features were significantly correlated with prodromal symptoms.

Conclusions: Findings support the utility of automated speech analysis to measure subtle, clinically relevant mental state changes in emergent psychosis. Recent developments in computer science, including natural language processing, could provide the foundation for future development of objective clinical tests for psychiatry.