We need to forget things to make space to learn new things, scientists discover

March 21, 2016

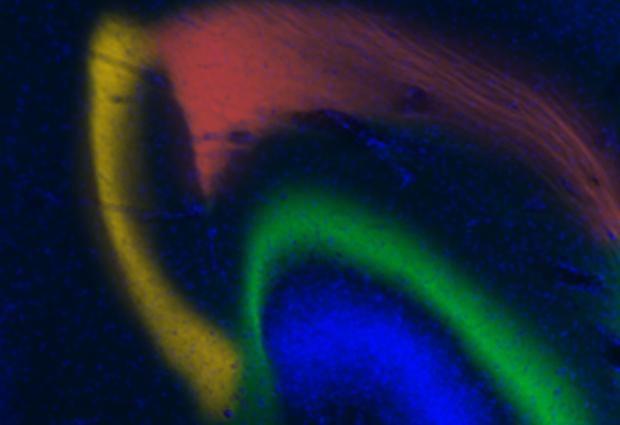

The three routes into the hippocampus seem to be linked to different aspects of learning: forming memories (green), recalling them (yellow) and forgetting them (red) (credit: John Wood)

While you’re reading this (and learning about this new study), your brain is actively trying to forget something.

We apologize, but that’s what scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and the University Pablo Olavide in Sevilla, Spain, found in a new study published Friday (March 18) in an open-access paper in Nature Communications.

“This is the first time that a pathway in the brain has been linked to forgetting — to actively erasing memories,” says Cornelius Gross, who led the work at EMBL.

Working with mice, Gross and colleagues studied the hippocampus, a region of the brain known to help form memories. Information enters this part of the brain through three different routes. As memories are formed, connections between neurons along the “main” route become stronger.

When they blocked this main route (dentate gyrus granule cells), the scientists found that the mice were no longer capable of learning (in this case, a specific Pavlovian response).* But surprisingly, blocking that main route also resulted in its connections weakening, meaning the memory was actually being erased.

Limited space in the brain

Gross proposes that one explanation: “There is limited space in the brain, so when you’re learning, you have to weaken some connections to make room for others,” says Gross.

Interestingly, this active push for forgetting only happens in learning situations. When the scientists blocked the main route into the hippocampus under other circumstances, the strength of its connections remained unaltered.

The findings were made using genetically engineered mice, but the scientists demonstrated that it is possible to produce a drug that activates this “forgetting” route in the brain without the need for genetic engineering. This approach, they say, might help people forget traumatic experiences.

* But if the mice had learned that association before the scientists stopped information flow in that main route, they could still retrieve that memory. This confirmed that this route is involved in forming memories, but isn’t essential for recalling those memories. The latter probably involves the second route into the hippocampus, the scientists surmise.

Abstract of Rapid erasure of hippocampal memory following inhibition of dentate gyrus granule cells

The hippocampus is critical for the acquisition and retrieval of episodic and contextual memories. Lesions of the dentate gyrus, a principal input of the hippocampus, block memory acquisition, but it remains unclear whether this region also plays a role in memory retrieval. Here we combine cell-type specific neural inhibition with electrophysiological measurements of learning-associated plasticity in behaving mice to demonstrate that dentate gyrus granule cells are not required for memory retrieval, but instead have an unexpected role in memory maintenance. Furthermore, we demonstrate the translational potential of our findings by showing that pharmacological activation of an endogenous inhibitory receptor expressed selectively in dentate gyrus granule cells can induce a rapid loss of hippocampal memory. These findings open a new avenue for the targeted erasure of episodic and contextual memories.